No Usability Without Accessibility – Commonalities and Differences Of Usability and Accessibility

Julia Undeutsch

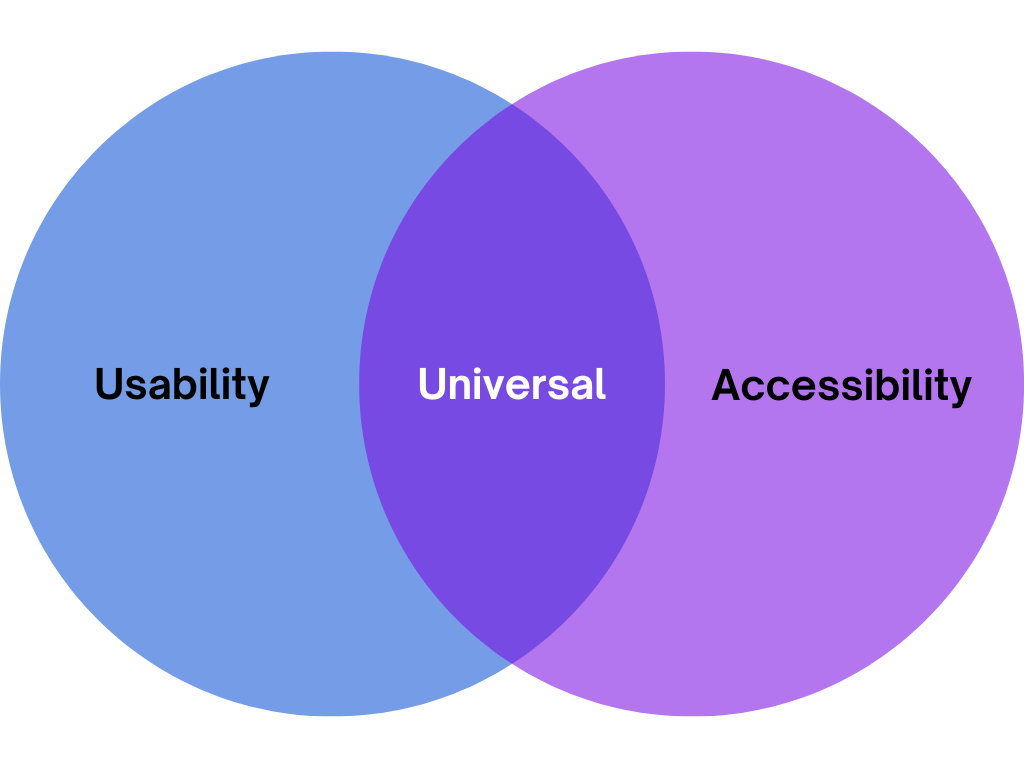

Usability and accessibility are closely related aspects of web development. Some mistakenly think that these two terms are interchangeable, even though they are different, their goals, approaches, and guidelines can overlap significantly, and one (accessibility) can exist without the other (usability).

Even if the website is accessible according to WCAG guidelines, it may not be usable. Usability refers to the quality, satisfaction, and efficiency a person experiences when using your website. Conversely, a website may be considered usable by users even though it ignores accessibility guidelines.

It is most effective to consider them together when designing and developing websites and applications. Using only one of the two approaches could result in an inaccurate assessment of your website's usability. Hence, keeping both usability and accessibility in mind when evaluating your website will ensure that all users get the best possible user experience.

Let's make the connection between the two terms while outlining their commonalities and differences after establishing a common baseline of knowledge regarding website usability and website accessibility.

Defining Usability

Usability is about effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction. The definition of usability according to the International Standards Organization's ISO 9241 standard is:

"The extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use."

Accordingly, a website should be self-explanatory, obvious, and intuitive. It must be ensured that it operates well enough that a person with (below) average skills and experience can use the website for its intended purpose without becoming frustrated.

Usability determines:

- Learnability: How easy a design's user interface is to use and how functional a product or design is

- Efficiency: Whether users can perform these tasks quickly

- Memorability: Whether users can remember how to perform these tasks after not using the interface for a while

- Error-proneness: The number of errors, the severity of errors, and how errors are fixed in the interface (the site should be designed to avoid errors or, if a user makes an error, to help them fix it)

- Satisfaction: Whether the design satisfies users (user experience)

Defining Accessibility

Similar to usability, accessibility is about enabling people with disabilities, including those who use assistive technologies, to use a website, tools, and technologies effectively.

Thus, accessibility increases the chances that more people will be able to use a website regardless of their abilities, which in turn increases usability.

Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the Wold Wide Web, says that:

“The power of the Web is in its universality. Access by everyone regardless of disability is an essential aspect.”

Accessibility is determined by POUR:

- Perceivable: Every user must be able to perceive content on the web through at least one of their biological senses

- Operable: Every user must be able to navigate into, use, navigate through, and exit the web components regardless of what input device they use

- Understandable: Every user must be able to understand the content and interfaces on the website.

- Robust: Every user must be able to interact with your website on any browser or computer system, as well as assistive technologies

Overlaps and Differences between Usability and Accessibility

Although accessibility is primarily aimed at people with disabilities and impairments, such as low vision, many accessibility requirements improve usability for all users. A keyboard-friendly website, for example, benefits both users with motor disabilities and users who prefer a keyboard to a mouse.

An important connection between accessibility and usability is that without accessibility, people with disabilities who use assistive technology have no way to make up their minds about the usability of the software.

However, it is also quite possible that fixing accessibility issues may lead to usability issues. A good example would be adding alternative text to images that exceeds the recommended maximum character length of 150 characters. The image may now be accessible but listening to the alternate text creates major usability problems because alternate text cannot be paused, as is the case with normal text content, and some screen readers cannot read the entire text aloud if it is too long. It is a fine line to ensure that fixing accessibility issues does not lead to usability issues, and vice versa.

Accessibility is virtually a prerequisite for usability. Accessibility issues only occur when people with disabilities have difficulty using or accessing a website without problems. Usability issues generally affect all users, both users with and without disabilities.

A website that is both usable and accessible benefits a variety of users, including:

- People with visual, speech, or hearing impairments or disabilities

- People with physical, cognitive, and neurological disabilities

- People with low literacy skills, or who are not fluent in the primary language of the site

- People who use older technologies or devices as well as users of mobile devices

Testing for Usability and Accessibility – Best Practices

One without the other is not the best user experience. Accessibility without usability is a poor experience for all users. People with disabilities can nominally use the software, but no one (with or without disabilities) will enjoy it because of the usability flaws. And usability without accessibility is not only a poor user experience for people with disabilities, but also means lost revenue for some companies and the significant risk of very expensive lawsuits.

When it comes to accessibility testing, automated testing tools can quickly find smaller, more common problems on a website. And while automated testing is a good starting point, automated testing can only detect about 30% of errors and is therefore not sufficient on its own to be able to designate a website as accessible. It is therefore necessary to check each element manually as well. Accessibility testing is done, for example, by checking the website code to see if it complies with WCAG 2.2 AA guidelines, and further by using a screen reader.

Usability tests, on the other hand, can only be performed by humans. By testing usability with a wide variety of people, you can ensure that your website meets standards for quality, efficiency, and satisfaction. Having a diverse set of people, both those who use assistive technology on a regular basis and usability experts, testing the website can ensure that it works with a broad range of tools and technologies. People who work with assistive technology daily can provide detailed feedback on the user experience issues they face, and experts can address aspects of user experience that daily website users may not be aware of.

Conclusion

Accessibility is a component of usability. When accessibility and usability are treated together, it can lead to a more accessible and usable web for all.

Technical and physical limitations of users must be understood, the design and code must comply with WCAG 2.2 guidelines and must be tested thoroughly to achieve accessibility. Usability, on the other hand, is about the quality of experience a user has when interacting with the website, the efficiency with which the user can complete a task, and the satisfaction the user feels after completing the task.

Key points to keep in mind:

- Accessibility is a subset of usability

- While usability implies accessibility, the opposite is not necessarily true

- A website is not usable if it is not accessible

- An accessible website benefits all users, not just those with disabilities

Resources are linked throughout this post.

Further readings:

- Accessibility, Usability, and Inclusion | Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) | W3C

- Accessibility | W3C Standards Webdesign

- Planning and Managing Web Accessibility | Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) | W3C Planning and Managing Web Accessibility

- Inclusive Design | Microsoft Microsoft Inclusive Design

- The role of accessibility in a universal web | MIT The role of accessibility in a universal web

- User Centered Design | Interaction Design Foundation User Centered Design